Heat pump owners across Northern Europe and North America wake up and check-not boiler pressure-but an app on their phone. The graph shows how hard the outdoor unit worked at 3 a.m., how low the temperature dropped, how close the system came to its limits. Outside, a quiet fan spins where an old gas flue used to cough steam into the air. Inside, some people are warm and smug. Others are wrapped in two sweaters, wondering if they were sold a dream.

Governments keep promising “green” heating that works for everyone. Manufacturers swear their latest models can handle Arctic blasts. And yet, as energy prices wobble and cold snaps hit earlier each year, a question whispers under the hum of compressors and circulating pumps.

What if the future of heating can’t handle the very winters it’s meant to tame?

Frozen nights, warm promises: the real-life winter stress test

On a cul-de-sac in Leeds, Tom and Hannah stand at their living room window, watching sleet collect on the outdoor heat pump unit like powdered sugar. The installer promised comfort “down to –15°C, no problem.” The thermostat reads 18°C, but the room still feels slightly cool on the back of the neck. The radiators are lukewarm, not hot the way gas made them. The system runs almost constantly, a low mechanical murmur in the background of family life.

This is the new psychology of winter: less about roaring heat, more about quiet, persistent warmth. Some neighbors roll their eyes at the “spaceship” on the side wall. Others have started asking discreetly about operating costs. The gas-boiler crowd are secretly watching this experiment from behind their double glazing. If the heat pump makes it through February without drama, they say, maybe we’ll think about it.

Across the Atlantic, in rural Maine, it’s the same story told in a harsher climate. Megan’s small farmhouse now runs on two high-efficiency air-source heat pumps, installed with generous state rebates. At –5°C, she’s thrilled: the living room is a cozy 21°C, and her electricity bills are lower than with oil. During a brutal polar vortex week, though, outside temperatures fall to –23°C overnight. Her pumps still work, but they wheeze closer to their limits, pulling backup power from old baseboard heaters. The system doesn’t fail; it just loses its effortless magic and starts to look like math on a spreadsheet again.

In Norway, where heat pumps are practically a national sport, statistics tell a calmer story. More than 60% of households use them, many in regions that routinely hit –20°C or lower. The trick is boring and unglamorous: proper insulation, larger radiators or underfloor heating, and units sized for design temperatures that reflect real local extremes. Where that groundwork exists, the pumps shrug off cold snaps. Where it doesn’t, users end up on social media, posting photos of ice-encrusted outdoor units and asking why their “eco miracle” can’t get the living room above 17°C.

The logic behind all this drama is simple physics. Heat pumps don’t create heat; they move it. At mild temperatures, they move a lot of heat for little electricity, which is why their efficiency numbers look almost magical. As the air gets colder, there’s less free heat to harvest, so the pump works harder and its efficiency drops. Modern cold-climate models can keep going impressively far below zero, but not with the same ease. At some point, electric resistance heaters or gas backups kick in. That point-and how often you reach it-determines whether your winter feels like a green success story or an uncomfortably expensive compromise.

Making a heat pump actually work in a real winter

The owners who glide through winter without drama usually share one unsexy habit: they treat their homes like a system, not just a collection of gadgets. Before the heat pump goes in, they blow insulation into attics, seal gaps around windows, sometimes even increase radiator sizes or add low-temperature underfloor circuits. They ask their installer for heat-loss calculations, not just “what size unit fits on that wall?” Then they run the whole thing differently from a boiler: low and slow, with steady temperatures rather than big on-off swings.

That shift in mindset changes daily routines. Instead of blasting the heat for an hour in the morning, they might set 19–20°C all day and nudge it down slightly at night. They learn that turning a heat pump off “to save money” on a freezing day is usually a false economy, because dragging the house back up from cold consumes power. It feels odd at first, especially if you grew up with hot radiators and clanking pipes. But after a few weeks, the constant, gentle warmth starts to feel normal. The drama shifts from “is it working?” to “how low can I keep the flow temperature and still feel comfortable?”

On a more emotional level, using a heat pump in harsh winter means accepting that comfort looks a little different. On the coldest evenings, you might wear thicker socks and still feel good about your choice, because operating costs stay predictable and the air feels clean. You might rely on a small wood stove, an infrared panel in a home office, or even a simple heated throw on the couch instead of cranking the whole house. On a human scale, that’s how people actually live. On a policy flyer, it’s all neat efficiency charts and payback periods. In reality, it’s one room that needs to be toasty because a baby sleeps there, and another you’re fine keeping at 17°C because it’s just for storage.

Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every day. Nobody spends all winter tweaking flow temperatures and logging COP values in a spreadsheet, even if enthusiasts pretend to online. Most people want to set it and forget it. That’s where decent controls, weather compensation, and smart thermostats come in. They quietly juggle outdoor temperatures and heating curves in the background, smoothing out what would otherwise be constant fiddling. When they’re set up properly, the whole “green heating” experience starts to feel less like a science experiment and more like everyday life-with a slightly nerdy twist.

Costs, illusions, and the quiet middle ground

Money is where the dream either hardens into reality or cracks. Up front, heat pumps in many countries still cost double or triple what a gas boiler costs, even with subsidies. For a mid-terrace house in the UK, a full system can easily run £8,000–£12,000 including new radiators and a hot water cylinder. In a cold U.S. state, dual-fuel setups that pair a heat pump with a high-efficiency gas furnace can also climb into five figures. That sticker shock leads some people to expect miracles. They want a bill that drops by half and a living room that feels like a ski lodge. When those expectations meet the physics of real winters and old brick walls, resentment sets in.

Operating costs in extreme cold are trickier to predict than glossy brochures suggest. If electricity is cheap and your home is well insulated, a heat pump can look like a long-term bargain even during cold snaps. Where power prices are high or rate structures are unfair, each extra kilowatt-hour in a blizzard hits harder. Some early adopters-especially those pushed into rushed installs by subsidy deadlines-now share screenshots of winter bills that look uncomfortably close to what they used to pay for gas. The technology didn’t “fail”; the assumptions about pricing, insulation, and user behavior did. They ended up paying to heat the street-just with a more sophisticated machine.

There’s also a social gap that doesn’t fit neatly into climate-policy slides. Heat pumps work beautifully in new, well-sealed homes or in countries that have spent decades improving building standards. In drafty rentals or modest older houses, the math is harsher. Landlords have little incentive to invest when tenants pay the bills. Lower-income households get hit twice: poor insulation and limited access to financing for upgrades. They’re the ones most likely to feel that “green” heating is a luxury for suburban early adopters with enough savings to fix the rest of the house first. That’s not a technical failure so much as a political one.

When you look past the noise, a quieter, more nuanced picture emerges. In Scandinavia, in parts of Canada, and in mountain towns in France or Austria, heat pumps already make it through brutal winters without drama. Where they fall short, it’s usually not the compressor giving up; it’s the human context: oversold expectations, under-insulated houses, rates that favor fossil fuels. The technology sits in the middle-neither miracle nor scam. A tool that makes sense in some conditions, less so in others. The future of “green” heating probably isn’t a single silver bullet, but a messy mix: heat pumps where they shine, district heating in dense cities, modern gas or hydrogen hybrids for the coldest corners, and a lot of boring insulation work nobody posts on Instagram.

| Key point | Details | Why it matters to readers |

|---|---|---|

| Cold-climate models are not all equal | Look for units tested and rated to at least –15°C, ideally –20°C or below, with a published COP at those temperatures-not just at +7°C. Brands often have specific “cold climate” lines with stronger compressors and smarter defrost cycles. | Helps you avoid buying a unit that looks great in brochures but struggles during the cold snaps that define your heating season. |

| Low flow temperatures are your friend | Designing the system so it can heat your home with 30–45°C water (through larger radiators or underfloor circuits) keeps efficiency high even in frost. High flow temperatures (55–60°C) make the pump work harder and reduce savings. | You’ll feel it directly on winter bills: every degree you can lower flow temperature tends to reduce operating costs while keeping rooms comfortable. |

| Backup heat is a strategy, not a failure | Many setups in very cold regions include a small wood stove, infrared panel, or an existing gas/oil boiler that only runs when temperatures plunge. Controls can be set so backup only turns on at a chosen outdoor temperature. | Makes a heat pump feel less like an all-or-nothing gamble and more like part of a resilient plan, especially during extreme cold events. |

Living with a heat pump when the temperature drops

If you already own a heat pump, the most useful “winter hack” isn’t a gadget. It’s learning your system’s rhythm before the worst cold hits. On a cool-but not freezing-week, test your settings: lower the flow temperature a few degrees, watch how the house responds over 24 hours, then adjust. Try a slightly higher set point overnight and see whether mornings feel different. Build a sense of how quickly your home loses heat and how gently the pump can pull it back.

When that knowledge becomes instinct, a cold snap feels less like panic and more like a stress test you’ve practiced. You already know which rooms struggle and where a cheap fix-a draft stopper, thicker curtains, a door kept shut-makes a big difference. You also know the tipping point where backup heat makes sense, not as defeat, but as a deliberate choice. That might be the night you light the wood stove or switch on an electric panel in the home office and smile at how much of the house is still running on the pump.

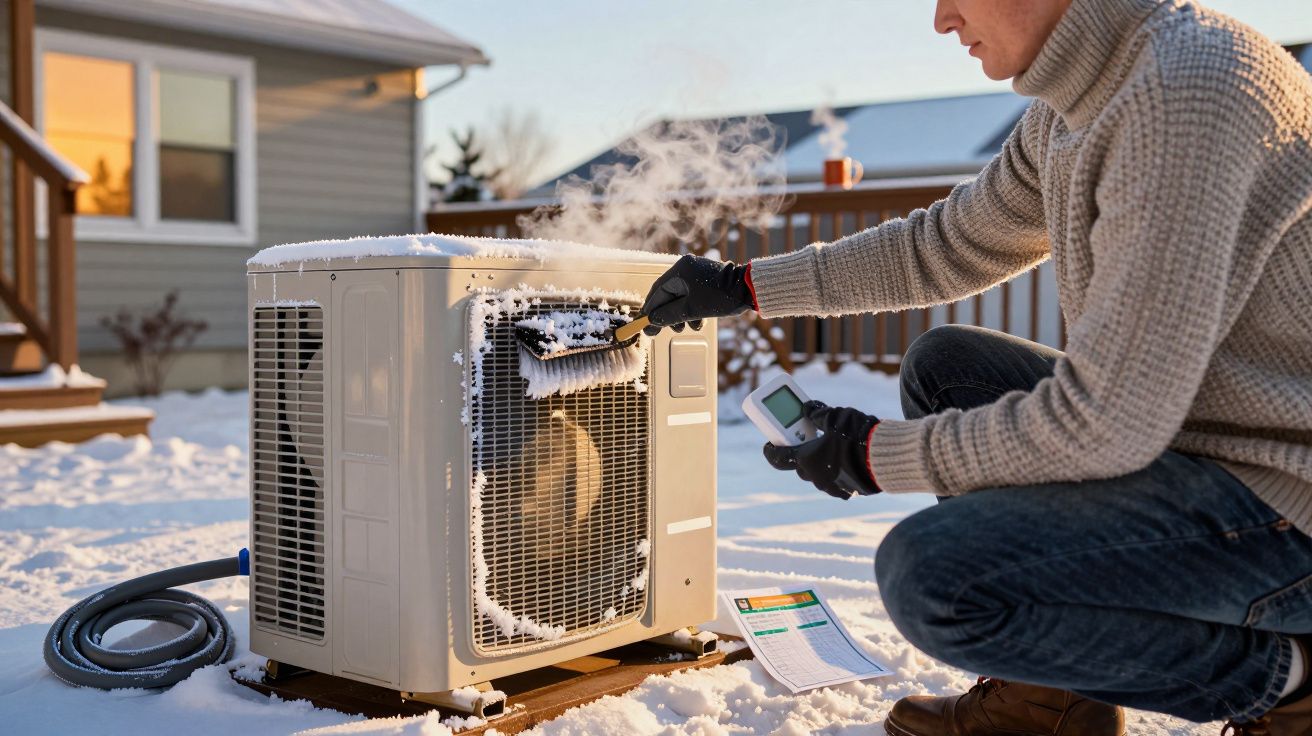

On the other hand, there are very human mistakes almost everyone makes the first winter-and they don’t mean you “failed” at being green. People turn the pump off when they leave for the day, then wonder why the house feels icy at 8 p.m. They set thermostats to 24°C “just to see,” then panic at the meter. They block the outdoor unit with bikes, trash bins, or snow piles, and the system wastes energy fighting its own environment. Installers don’t always take the time to explain that a heat pump is more like a refrigerator than a boiler in how it prefers to run: steady and unhurried.

On a bad day, those little missteps add up to regret. On a good day, they’re just part of learning a new kind of winter. The empathy often missing from policy debates is simple: people are tired, busy, sometimes cold, and anxious about money. They need systems that tolerate imperfection, not just perfect use. The best winter stories from heat pump owners aren’t about flawless graphs; they’re about small tweaks that made the house feel like home again.

“The turning point for me,” says Jakob, who lives near Munich, “was when I stopped treating the heat pump like delicate lab equipment and started treating it like a slightly stubborn old car. It wants the right fuel, a clear driveway, and not being thrashed from cold. Once I gave it that, our winters got boring again-in a good way.”

For many households, a few grounded checks make the difference between a satisfying winter and a storyline of disappointment:

- Walk around and feel for drafts on a windy evening; cheap sealing tape can save “bad rooms.”

- Keep at least 30–60 cm (12–24 inches) of clear space around the outdoor unit, and clear snow from the intake after storms.

- Ask your installer (or a local expert) to enable weather compensation so the system anticipates cold instead of chasing it.

This is the quiet craft of living with “green” heat through real cold. Less about ideology, more about noticing your own home. About accepting that on some nights you might need a blanket and a backup plan-and still feel a strange satisfaction that your main source of warmth is pulling heat out of freezing air with nothing more than electricity and a bit of physics.

Where winter might take the “green heating” dream next

The deeper question behind all these stories isn’t whether heat pumps work in cold climates. We already know they can-and do-from Oslo to Ottawa. The harder question is who gets that performance, at what cost, and under what conditions. A well-designed system in a tight, well-insulated house feels like living in the future. A rushed install in a drafty semi feels like being stuck between worlds, paying for a promise that hasn’t fully arrived.

Over the next decade, pressure will move in one direction. Power grids will need to accommodate millions more electric heating systems. Policymakers will have to decide whether to shape rates and subsidies so low-carbon heat is genuinely attractive on the coldest days-not just in mild shoulder seasons. Manufacturers will keep pushing the limits of what compressors can do in sub-zero air, while critics keep posting photos of frozen fan blades to make their case. The culture war around “green” heating will be fought in living rooms and on energy bills long before it’s settled in legislatures.

Amid all that noise, one small but powerful factor remains in the hands of ordinary owners: the stories they tell each winter. If those stories are about homes that stay quietly warm at –10°C without financial panic, the technology will spread-neighbor by neighbor, street by street. If they’re stories of disappointment and blame, heat pumps risk becoming a symbol of environmental overreach. As this winter bites, the outcome isn’t predetermined. It lives in tens of thousands of homes where people are listening, shivering a little-or not shivering at all-and wondering what kind of warmth the future really holds.

FAQ

- Do heat pumps actually work in very cold climates? Yes-if they’re the right type and properly designed for the building. Cold-climate air-source models in places like Sweden, Norway, and parts of Canada routinely operate at –20°C and below, often with some form of backup heat for the harshest nights.

- Will my heating bills go down in winter with a heat pump? They can, but not automatically. Savings depend on your insulation level, how low you can run the flow temperature, your local electricity and gas prices, and whether you frequently rely on backup resistance heat during cold snaps.

- Why does my house feel cooler with a heat pump than with a gas boiler? Heat pumps usually run radiators at a lower temperature, so they feel warm rather than hot to the touch. The overall air temperature can be the same, but without that “radiator blast,” some people initially perceive it as cooler.

- Should I turn my heat pump off when I go to work? In a cold spell, turning it off completely often backfires. Letting the temperature drop slightly-then maintaining steady background heat-usually costs less than reheating a cold, drafty house every evening.

- Do I always need a backup heating system? Not always. In milder climates and very efficient homes, a properly sized heat pump can handle the whole season. In regions with regular deep freezes, many people keep a secondary source-gas, wood, or electric panels-as insurance for rare but intense cold waves.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment